Roughly five minutes into Tom Clancy’s The Division, you will begin shooting at (conveniently) armed enemies in the streets of Brooklyn. These enemies wear hoodies and baseball caps. They uniformly brandish semiautomatic handguns or submachine guns that they tend to hold sideways while firing at you. These enemies belong to a faction known in-game as the Rioters, and they are one of four types of enemies you will encounter throughout Manhattan once you begin the game proper.

The tagline to The Division is “Take New York Back” and after encountering the Rioters, one has to wonder exactly who we are taking New York back from. The simple answer would be “other Americans” but the more accurate answer would be “undesireables.”

To catch up the people who haven’t read up on the game, The Division is your bog-standard Tom Clancy fare. Right-wing nonsense from start to finish, the game takes place in Manhattan after the outbreak of a human-made bioweapon based on smallpox and distributed on paper currency during Black Friday. Dubbed the “Dollar Flu,” this disease apparently wipes out a great deal of New York’s population (within a matter of weeks given the Christmas decorations all over the place) and society itself collapses as a result. The Dollar Flu is spreading worldwide (this fact is not well-communicated to the player), and government agents are sent in to restore law and order as well as work on a vaccine for the disease.

Players are cast in the role of one of these agents, members of the titular Division. The Division is a secretive government organization which is made up of civilian operatives, sleeper agents who are activated in times of great crisis to “ensure the continuity of government.” Yes, that’s just as ominous as it sounds. You are activated in the beginning of the game, and spend the bulk of the story “taking New York back” from anyone standing in your way.

The Division does have a tenuous basis in reality. Directive 51, signed by President George Bush in 2007, is a mysterious executive order that rolls the three branches of American government into a single entity administered by the President in the event of a catastrophic disaster. Not much more is known, as the exact wording of the document is a secret. Directive 51’s existence is widespread public knowledge. While most Americans would probably find this document to be incredibly troubling, in the world of The Division, Directive 51 is depicted as being ultimately good.

Division agents are empowered with “ultimate authority” to do whatever needs to be done to maintain law and order. Mostly this translates to going where you want, killing anyone who is also armed, and taking whatever you please. The game depicts the Rioters as bad because they are looting, but the game is completely fine with the player character entering private residences and taking whatever you can find.

So who are the people opposing you in your mission? Who are you taking New York back from? The Rioters are the first enemies you encounter, and they are representative of racial minorities and the poor. From their manner of dress and speech to their weapons and typical environs, the Rioters are obvious caricatures of non-white and impoverished New Yorkers.

Next up are the Cleaners, former sanitation workers who have built their own hazmat suits and flamethrowers and are set about the self-appointed task of eradicating the disease, and they don’t care whether the infected are still alive. Led by the charismatic Joe Ferro, the game depicts them as unintelligent fanatics, made up of the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. The Cleaners take some of the most unappreciated people in America and cast them as the villains.

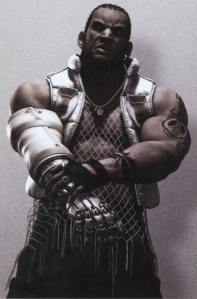

Then we have the Rikers, who are former prisoners who have escaped and are now heavily-armed and violently opposed to going back to prison. Their leader is Larae Barrett, who is depicted as being as bloodthirsty as she is theatrical. The Rikers hit every American fear of convicts that there is. Every single Riker is a killer (supposedly because if you weren’t willing to kill, you were killed) and are only interested in killing cops/guards and causing as much mayhem as possible. Why the Rikers don’t try to dress in civilian clothes and disappear into the remaining population is never explained. If you have played the Arkham games, you have seen this brand of cartoonish villainy before.

Finally there is the Last Man Battalion, a private military company hired to protect the New York elite and then abandoned after the quarantine was put in place. They answer to Colonel Charles Bliss, who is basically Kurtz from Apocalypse Now with the serial number filed off. Of all the enemy factions, the LMB are possibly the only ones who are somewhat understandable. After all, real-life PMCs like Blackwater have not painted a favorable picture. Even then, the LMB are still average people stuck in a shitty situation, but are treated like fodder with no redeeming qualities.

The game does the best it can to give you reasons to hate the various factions. Rioters threaten a journalist with rape. A Cleaner burns an asthmatic childhood friend alive at the drop of a hat for merely coughing. Rikers burn a room full of people to death with a molotov for the fun of it. The LMB breaks into the homes of affluent New Yorkers and drags them off for their own protection. This is a concerted effort to make the player feel as though murdering these enemies is completely justified. This does not change the fact that the player is routinely gunning down American citizens in the street without due process, in clear violation of their Constitutional rights.

And sometimes the game calls your actions into question. Paul Rhodes, an engineer who works in your base of operations, openly mistrusts you and the Division as a whole. He questions whether your absolute authority jives with American ideals (it doesn’t), and acts as a strawman for the game’s right-wing political philosophy. In the end, Rhodes’ questions are dismissed by the over-the-top brutality of the world, as you continue to prove that the Division is a necessity, regardless of how ugly it may be. The normal soldiers of the game are shown to be inept and constantly in need of your help, helpfully displaying to the player that their actions are necessary and righteous.

The reason for this is again rooted in a deeply conservative outlook that is characteristic of all Tom Clancy dreck. One of the largest cities in the world collapses into anarchy within a matter of weeks, with roving gangs of murderers and thieves roaming the streets in the dead of winter. The Division wants you to believe that every single person is a bad day away from either becoming a cold-blooded killer for a can of food or turning into a helpless coward in need of an authoritarian. As you clear out enemies and complete missions, some places begin to return to a kind of normalcy. People can be found out talking in the streets, or out cleaning, moving things back into homes. But again, this occurs only after you have come through, restoring the law with only your gun and your wits. People in The Division are either monsters or meek, with no in-between.

This all contributes to the well-known conservative atmosphere of fear and paranoia. Buy guns, stock up on food, buy protection, and fear thy neighbor. All of this is championed by The Division, which proudly espouses the idea that our civilization is barely keeping us from killing each other at any moment. The game would have you believe that you can trust no one, and that your community will fall apart at the slightest prodding. Even as a cynic, I find this to be a bleak outlook.

And when you look at the kinds of enemies in The Division, you see exactly who the game is suggesting we “take New York back” from. Minorities, the poor, the working-class and the condemned are all seen as obstacles to be overcome. And if you’re wondering exactly who the prototypical Division agent is? The game’s promotional art prominently features a generic white male character front-and-center. To its credit, the game allows you to create a wide variety of characters, and the only other friendly Division agent you meet is an Asian woman.

The game seems to be on some level aware of itself. The main villain of the game is Aaron Keener, a rogue Division agent, and the Dollar Flu was developed by a man named Gordon Amherst (worry not, Clancy fans, Amherst did it all because he is an environmentalist who believes humanity is a threat to all life on Earth). It feels as though some members of the writing team were attempting to send a message in line with Clancy’s gross politics, while others were satirizing elements of the game’s right-wing nonsense.

This disconnect characterizes the overall story of The Division. The game is set in New York City, but shows us a version of reality filled with cartoonishly evil stereotypes and presents a narrative that is almost completely uncritical of the fascist protagonists. There are so many missed opportunities here, more interesting stories to be told. The inherent anti-capitalist message of the “Dollar Flu.” The ethics of stealing to survive and who is allowed to take what versus who is branded as a criminal. The overstepping of governmental powers in pursuit of maintaining order. Regular people knowingly doing the wrong things for the right reasons. All of these themes exist in The Division, but are unexplored in favor of a far safer, more boring narrative that serves as pro-authoritarian propaganda.

The Division is published by Ubisoft, a French company, and developed by Massive, a Swedish studio. I am not accusing the writers, developers, or publishers of consciously pushing an American right-wing political agenda through this game. Oftentimes, products like this are the result of straightforward intentions and a lack of introspection. What’s most troubling to me is that a foreign company can so easily create a game like The Division accidentally. Our anxieties and fears so saturate our cultural exports that The Division is nearly inevitable. The game shines a light on an ugly aspect of our current political landscape, however unintentionally. This is not a mark against the game. I think that through examination and critique we can use this to learn more about ourselves and hopefully improve.